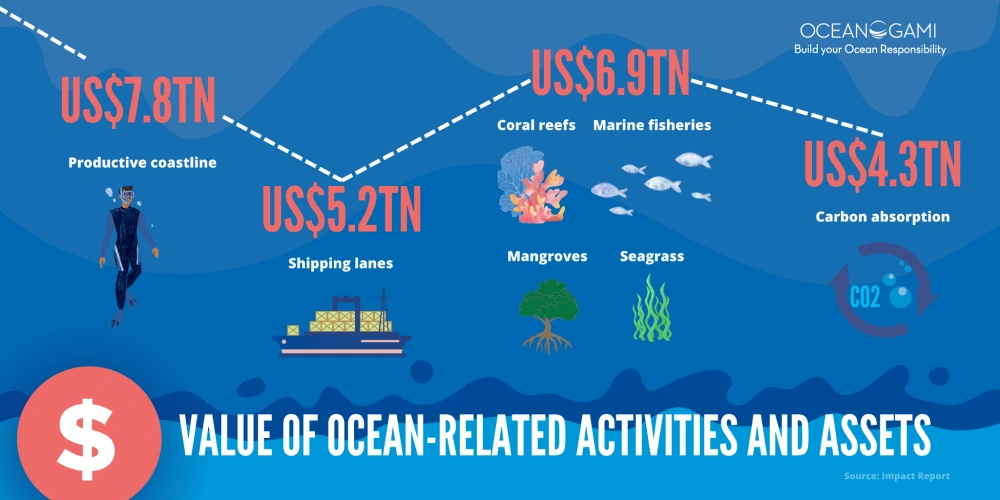

The health of our oceans hangs in the balance. Today, more than ever, we are called to act decisively and collaboratively to protect and conserve marine biodiversity. One of the most critical tools in restoring endangered marine life and in supporting economic and social prosperity is the establishment of Marine Protected Areas (MPA). There are 18,431 marine protected areas in the world (Protect Planet, 2023). The specific benefits accruing from MPAs are multifaceted. The monetary value of the services provided by marine ecosystems in MPAs globally can be observed in the figure 1 (Impact report).

MPAs are areas in the ocean where all types of activities are regulated, from extractive use to recreational use. Because many different activities can be practiced in the same area of the ocean, the creation of marine protected areas influences a large number of stakeholders, which is why the collaboration and active participation of all interested groups is necessary in order to ensure good management and the success of MPAs. Taking this into account, the involvement of the private sector within marine protected areas is of vital importance in order to improve the state of our oceans. In this article, we explore how the private sector can have a key role in sustaining MPAs.

Figure 1. summary of ocean ecosystem service globally. Source: Impact Report

Successful case studies on private sector engagement

Good practices are important to inspire future businesses. Here are some examples of the economical benefits from MPAs in fisheries and aquaculture, maritime tourism, and potential sectors of the blue economy.The synergy of MPAs financed and/or managed by private sectors impact fisheries and aquaculture sectors observed by the increasing of fishing productivity in Columbretes Islands Marine Reserve, Spain (Goñi, Quetglas and Reñones, 2006), Cerbère Banyuls; Carry-le Rouet, France (Goñi et al, 2008; Forcada et al, 2009), Gulf of Castellamma re, Italy (Whitmarsh et al, 2002) and generating new income with fishing activities diversification e.g. Implementing a brand or quality certification for products linked to the MPA in 66 MPAs in the North East Atlantic – England, France, Spain and Portugal – (Álvarez Fernández et al, 2017).

Other sector impacted by is the Maritime tourism, which observed increasing of revenue in the Recreational Fisheries and Scuba Diving in several MPAs in Southern Europe (Alban et al, 2008), Lyme Bay – UK (Rees et al, 2010) and Cozumel (Lara-Pulido et al, 2021); in activities related to angling for Recreational boat fishers in Cap de Creus in Spain (Lloret et al, 2008) and in the number of tourists observed by hotels and tourism agencies as tourists believe that the MPA constituted a significant advantage in comparison to other destinations (Oikonomou and Dikou, 2008).

Hotels and tourism agencies especially benefit from the association with a MPA so-called “designation effect” to increase the Business services and products reputation and profile as Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) companies committed to UN SDGs,therefore, attracting more visitors (Pantzar et al, 2018). However, this strategy needs to come together with a realistic impact of the business regarding environmental conservation. Science-based evidence points out the possibilities of the corporation to expand on the most effective ways to maximize sectors such as tourism without compromising the marine environmental health. As seen in the study carried out by Dixon et al (1995), which calculated how many divers can visit the Great Barrier Reef before damaging the ecosystems, allowing to forecast future scenarios helpful for MPAs management plans. Aspects to be considered when evaluating the appropriateness of the business sector in managing MPAs.

Closed-loop system – the case of Chumbe Island Coral Park

Chumbe Island (Tanzania) is an example of financially self-sustaining MPA in the World for the first privately managed MPA with public-private partnerships. The closed-loop system is when all revenue generated from business activities are allocated to the conservation management and site operation of the MPA with zero economic leakage.

The success of the business management model of the Chumbe Island Coral Park is not only due to the closed-loop system but also the active participation and integration of business corporations and local communities. The shared role in managing MPA progress monitoring and decision making create opportunities of income generation for local enterprises such as boat handlers (former fishers), farmers, sustainable fisher, Women’s handicraft collectives and Local community artisans, reducing conflict and enhancing local economies.

But the secret to succeed in this endeavor is not restricted to the financing matter but also the trust built among business and stakeholders and, the choice of the right private sector partner (UNEP, 2023) supported by science-based evidence in order to promote and expand best practices based on principles of sustainability. When well-designed, well-implemented synergies among diverse sectors and MPAs can bring opportunities for genuine ‘win-wins’ benefiting private sector, marine environment and local communities.

Oceanogami’s Role in Advocacy

At Oceanogami, we firmly believe that businesses investing in preservation initiatives will bolster marine ecosystems and stimulate sustainable economic growth. We remain committed to fostering such collaborations and leading the path towards healthier seas and a sustainable future.

In Conclusion

The involvement of the private sector in marine conservation is not just an option; it’s a necessity. By harnessing the collective power of businesses, governments, local communities, and nonprofit entities, we can ensure the survival of our oceans and the myriad species that call it home. It’s a win-win for our planet and economy, proving that when we come together, a sustainable future is achievable.

This is part of the Oceanogami Ocean Corporate Series. A series that aims to give further insight into the elements and topics needed to understand the intersectionalism of businesses and organizations and environmental sustainability and the role they can play in making a positive impact in marine conservation. Stay tuned for more!